Censorship in Afghanistan: Death to journalists

By Robert Maier

Published in Kabul Press (Thursday 11 March 2010)

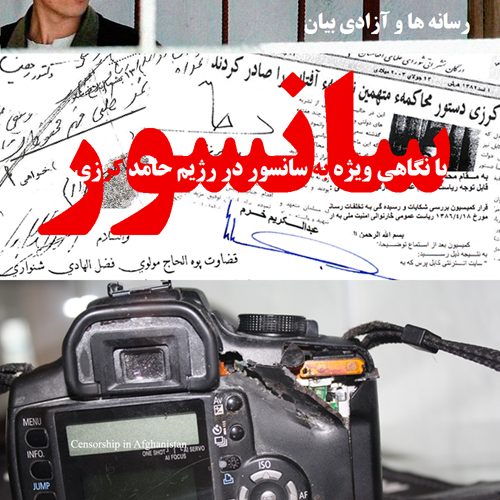

Since the beginning of the Karzai regime in 2002, twenty Afghan journalists have been murdered, and more than 200 violent physical attacks against journalists have been logged. Scores have fled Afghanistan after receiving threats against them and their families. Journalists have been sentenced to death, and several remain in jail after being arrested for their work. Radio and television stations, print media, and Internet services have been attacked, blocked, damaged, and even burned to the ground by government and other politico-religious agents and gangs.

As dozens of governments around the world pour billions of dollars and 100,000+ troops into Afghanistan to defend the Karzai government, it is an appropriate time to explore the human rights and legal issues regarding censorship and freedom of the press there.

Kabulpress’ founder and editor-in-chief’s most recent book, “Censorship in Afghanistan” just published by Norway’s IP Plans e-Books addresses this issue in a thorough manner. Written in the Dari language, it is the first book to explore the systematic suppression of free speech in Afghanistan that has been a feature of its ruling authorities for hundreds of years. Kamran experienced censorship first hand when he established Kabulpress.org in 2004, which was aimed at revealing corruption in the Afghan government and NGOs who were mis-handling millions of development dollars flowing into Afghanistan. He was detained several times by government agents and received numerous anonymous warnings about his work. The Afghan Secret Service tried to bribe him as a paid informant before he finally fled to India, where he was granted political refugee status by the U.N. and re-settled in Norway.

Censorship in Afghanistan/ ISBN 978-82-93037-00-2 E-book/PDF/ Download

There is a special focus on the administration of Hamid Karzai over the past nine years, when after the fall of the Taliban, Afghans hoped that a new era of freedom of speech was beginning. To the contrary, under the Karzai regime, the newly freed media has been suppressed through government statutes and actions, and violent extra-legal autocratic political and religion-based organizations, which the government has been unable or unwilling to control.

The content of “Censorship in Afghanistan” makes it clear why it is the first book ever on the topic. Censorship in Afghanistan has been constant, harsh and violent. Any media that discusses censorship and government or religious corruption and misdeeds is punished both physically and economically. TV, radio, and print media have learned that their staffs will be threatened, assaulted, and/or imprisoned, and their property will be confiscated or destroyed, if they present views contrary to or critical of the Afghan power structures (government, religion, and illicit drug industry). Staff journalists have learned, usually painfully, that they will be demoted or fired if they continue disfavored work. Independent journalists have been threatened, jailed, and murdered, if they displease the powers that be.

“Censorship in Afghanistan” includes interviews with several exiled Afghan journalists, including Parwiz Kambaksh, the 20-year old student whose death sentence for sharing an article about women in Islam spawned a global outcry over the Karzai administration’s stifling of free speech. Journalists who have fled to the West and been granted political asylum, even though they may work for international organizations such as Voice of America and the BBC, are afraid to speak out because their families back in Afghanistan may be harmed as a result. The arm of Afghan censorship proves to be quite long and effective.

Private businesses that advertise in censored/disfavored media are threatened by the same powers, receiving visits or anonymous communications from the gangs and officials who support the status quo. Therefore, media censorship is a black hole from which little or no information escapes, with a few exceptions, like Kabul Press and IFEX, which are based outside Afghanistan. The Afghan Communications Ministry categorizes Kabulpress.org as “pornography,” and with increasing success, blocks access to it on the Afghan Internet. This level of censorship of Kabulpress.org occurs in only two nations, Iran and Afghanistan, ironically at polar opposites in terms of support from the West. However given the growing cozy relationship of Karzai and Ahmadinejad, it is logical.

Currently, “Censorship in Afghanistan” is published only in Dari. It was funded by a grant from the Norwegian Non-fiction Writers and Translators Association to encourage Afghans to understand the depth and breadth of censorship in their country. Due to censorship, Afghan citizens and journalists have little knowledge of the problems. There is simply too much fear in the Afghan media to document these abuses.

As an e-book, “Censorship in Afghanistan” can be downloaded on personal computers in Afghanistan, thus avoiding the certain violent attacks Kabul booksellers would receive if they carried it. Printed copies are also available from the publisher for Dari speakers living in non-censoring countries.

Funds are not available now for an English version, but the author is hopeful they will surface. It would be an eye-opening source of information for Westerners whose governments spend billions to support the Afghan government, and for families with relatives risking their lives in the military or in NGOs that support the Karzai administration and its censorship. The 219 page book will be updated annually with relevant censorship news and information.

“Censorship in Afghanistan” includes the following nine chapters:

Chapter 1 focuses on the long, sad history of crimes against humanity and human rights abuse in Afghanistan of which censorship and illiteracy has been a centerpiece.

Chapter 2 introduces the general topic of censorship and specifically what occurs in Afghanistan. It discusses the enormous amounts of money that governments and NGOS have poured into Afghanistan to support a free media. Consultants have been paid huge sums of money to do this, but the net result over the past nine years is a situation that is nearly as bad under the Taliban.

Chapter 3 discusses who carries out the censorship, including Afghan security forces, the Taliban, the Ministry of Culture, various governors, warlords, commanders, and those involved in the massive drug trade. Add to that list, international troops, the Attorney General, Interior Ministry, Education Ministry, Finance Ministry, Parliament and other governmental institutions.

Chapter 4 discusses the phenomenon self-censorship for self-preservation, involving security, political and economic considerations, and social and cultural elements that must be considered by persons contemplating speaking out.

Chapter 5 catalogs the names and circumstances of journalists killed in Afghanistan since 2001. It includes both Afghan and foreign journalists. Additionally, it includes a list of journalists who fled Afghanistan after threats and attacks due to their work, and a calendar of both fatal and non-fatal attacks from 2001 to 2009.

Chapter 6 reviews the development of mass media in Afghanistan, after the fall of Taliban, including radio, TV, print, news agencies, independent journalists, the Internet, the mass media audience, and the quality of journalistic efforts.

Chapter 7 concerns journalists and other individuals and organizations dedicated to defending freedom of information in Afghanistan. They include the Committee to Protect Journalists, the International Federation of Journalists, the United Nations, the International Freedom of Expression eXchange, and Reporters Without Borders, which globally publicize attacks on journalists and free speech in Afghanistan.

Chapter 8 presents an overview of Afghan media law, and its various permutations including the creation of the government news agency Bhaktar, a history of various media laws going back fifty years, military censorship, Taliban media laws, and current trends in media law enabling legal censorship by the Afghan government.

Chapter 9 discusses possible solutions to opening up Afghanistan’s closed media world. They include programs to eliminate illiteracy, the transitional justice project espoused by former Finance Minister and 3rd place 2009 presidential candidate Dr. Ramazan Bashardost. It also provides a list of additional resources and sources used. Additional attachments include the latest media laws in Afghanistan enacted last year by its Parliament and copies of original government documents that encourage and promote official censorship.

“Censorship in Afghanistan” is a remarkable book that could spur needed change in Afghanistan. Afghans have suffered long and hard under the control of corrupt governments, war lords, drug lords, and religious autocrats. It is knowledge like this that will help set them free. It is particularly sad that the leading global news media and writers have been so silent on this topic for so long.

P.S.

“Censorship in Afghanistan ” was funded by a grant from the Norwegian Non-fiction Writers and Translators Association